The 14th Century was an interesting time in history. It was a time of global cooling, famine and the black death, when large swathes of the population died. The church was also in turmoil with the popes residing in Avignon in Southern France for much of this period, under the control of the French king, causing rival claims to the papacy to be brought from the Vatican and also Pisa in central Italy. This period (1309-1377) was known as the Babylonian Captivity and was succeeded by the Great Schism in 1378.

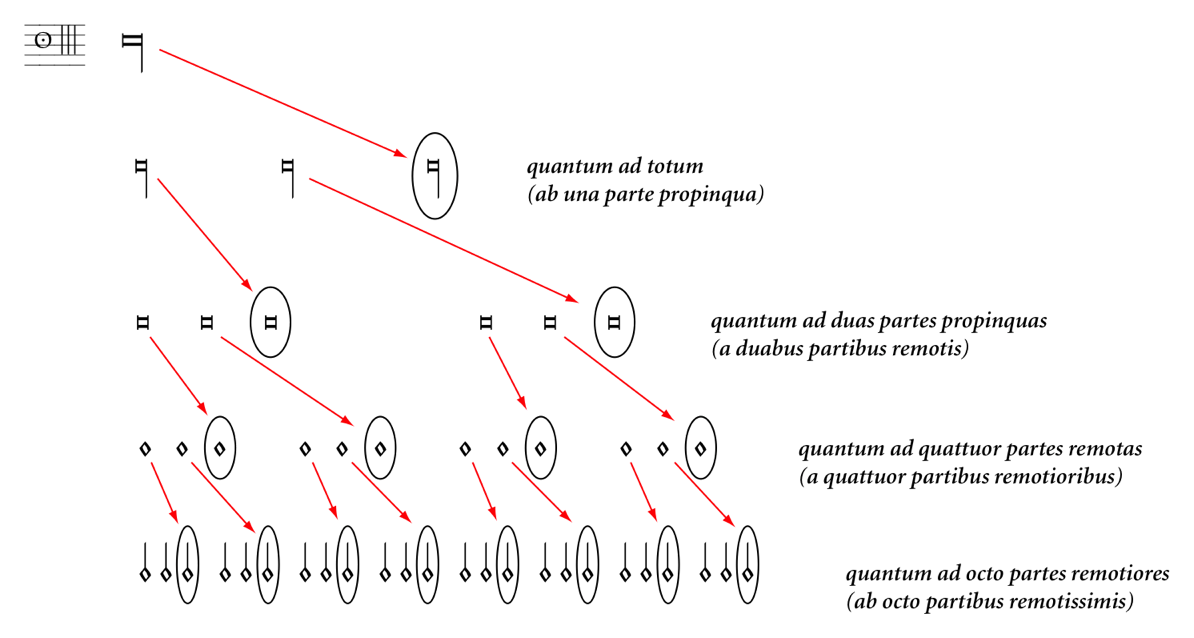

Ars Nova, or new art, came about in this period. It was a time of many changes and growth in music particularly in the realms of notation and rhythm. It was also the time when composers started to use dissonances in their music, straying away from the approved and perfect consonances of fourths and fifths. In the 13th century musical notes were grouped into threes, known as perfect time. This represented the Holy Trinity. As the 14th century progressed composers started to introduce rhythms using groupings of two notes and this became imperfect time. Notation also became more like what we have today.

It was not only a time of change in music. The artist, Giotto (ca. 1266-1337), one of the great artists living in this period, was the first person to start painting in the more realistic style we are used to today. The people depicted in his paintings were more lifelike and he started to experiment with the use of perspective rather than the two dimensional images used prior to that.

With the advent of mechanical clocks coming into regular use, it was possible for time to be measured accurately. This also meant that the rhythm and meter of music could also be measured more precisely whereas, earlier music could be interpreted in many different ways, dependent on who was performing it.

Modern transcriptions use bar lines to help guide the eye; motet notation had no bar lines, nor was polyphony written in score in France in this period. Musicians had to put the polyphonic lines together from a page that displayed the parts in individual blocks.

Margot Fassler, Music in the Medieval West (New York: Norton, 2014)

Margot Fassler, Music in the Medieval West (New York: Norton, 2014)

Guillaume de Machaut (ca. 1300-1377) was an important composer and poet of this period. He was keen to preserve his work, both religious and secular, so much of his music is able to be performed today. I recently sang Machaut's La Messe de Nostre Dame with a local choir and found it very straightforward to sing. It was more tonally acceptable to my ears than some of the earlier works we have listened to or tried to sing. It is believed to be the first polyphonic setting of the Mass Ordinary written by a single composer. Each of the six movements is written for four voices, the tenor with the duplum and triplum parts above and the contratenor moving against the tenor in the same vocal range.

This period also gave us the birth of the polyphonic song, also known as chansons. The upper (treble) voice became the principal line instead of the tenor. The tenor then became the supporting voice with a slower moving line without text. Added to this was a contratenor singing the duplum line and a faster moving triplum line in the treble range. Here is an example of a polyphonic song by Machaut.

As with every new development, Ars Nova had its dissenters. One of the most notable was Jacques de Liège (ca. 1260 – after 1330) who wrote Speculum Musicae (The Mirror of Music, ca. 1330), a treatise on music which is believed to be the longest surviving medieval treatise on music. He wrote,

Wherein does this lasciviousness in singing so greatly please, this excessive refinement, by which, as some think, the words are lost, the harmony of consonances is diminished, the value of notes is changed, perfection is brought low, imperfection is exalted, and measure is confused.

I think that, while change isn’t always a good thing, without the advent of Ars Nova, we would not have music in the form we have today. Music is ever evolving and what we deem experimental music in our current time may well be conceived as old fashioned and quaint by those listening to it 600 years from now. Ultimately it is down to personal preference. Do you prefer the plainsong of the 13th century or would you rather listen to the polyphony on the Ars Nova?

No comments:

Post a Comment